The Critical Role of Nonlinearity

Why do we need the activation function \(g\)? What happens if we just use a linear function, like \(g(z) = z\)?

Consider a network with multiple layers, but no non-linear activation functions between them. The output of one layer is just a linear transformation of its input. If we stack these linear layers:

Let the first layer be \(h_1 = W_1 x + b_1\). Let the second layer be \(h_2 = W_2 h_1 + b_2\).

Substituting the first into the second:

This can be rewritten as:

Let \(W_{eq} = W_2 W_1\) and \(b_{eq} = W_2 b_1 + b_2\). Then:

This is just another linear transformation! No matter how many linear layers we stack, the entire network will only be able to compute a single linear function of the input.

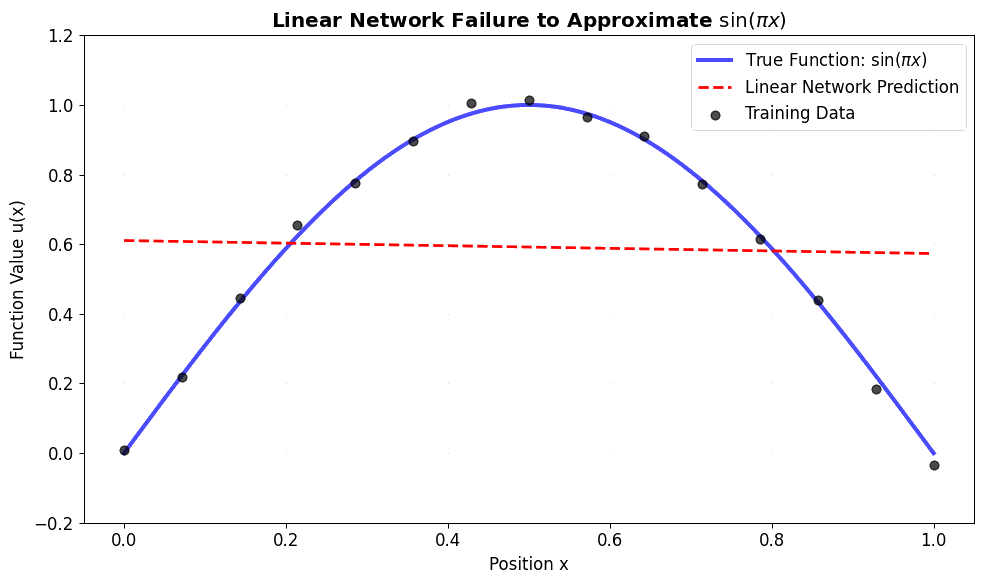

Linear network can only learn: y = mx + b (a straight line in 1D) But sin(πx) is curved - impossible with just linear transformations!

To approximate complex, non-linear functions like \(\sin(\pi x)\), we must introduce non-linearity using activation functions between the layers.

CVW material development is supported by NSF OAC awards 1854828, 2321040, 2323116 (UT Austin) and 2005506 (Indiana University)