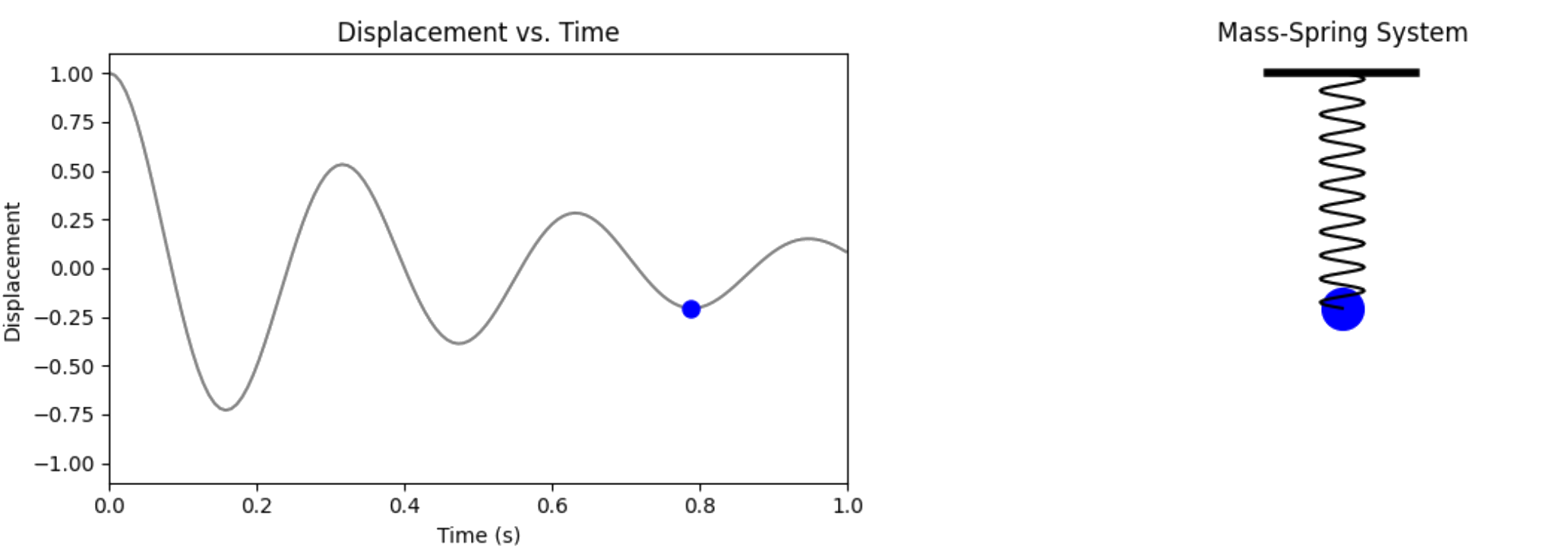

The Problem: A Damped Harmonic Oscillator

We begin with a concrete problem that everyone understands: a mass on a spring with damping. This is the perfect starting point because:

- Physical intuition: Everyone knows how springs work

- Mathematical tractability: We have an exact solution

- Clear demonstration: Shows why standard ML fails and PINNs succeed

The Physical System

A mass \( m \) attached to a spring (constant \( k \)) with damping (coefficient \( c \)). The displacement \( u(t) \) from equilibrium satisfies:

Initial conditions: \( u(0) = 1 \), \( \frac{du}{dt}(0) = 0 \) (starts at rest, displaced)

Parameters: \( m = 1 \), \( c = 4 \), \( k = 400 \) (underdamped: \( c^2 < 4mk \))

The Exact Solution

For underdamped motion (\( \delta < \omega_0 \) where \( \delta = c/(2m) \) and \( \omega_0 = \sqrt{k/m} \)):

where \( \omega = \sqrt{\omega_0^2 - \delta^2} \) is the damped frequency.

> This example is adapted from Ben Moseley's blog post.

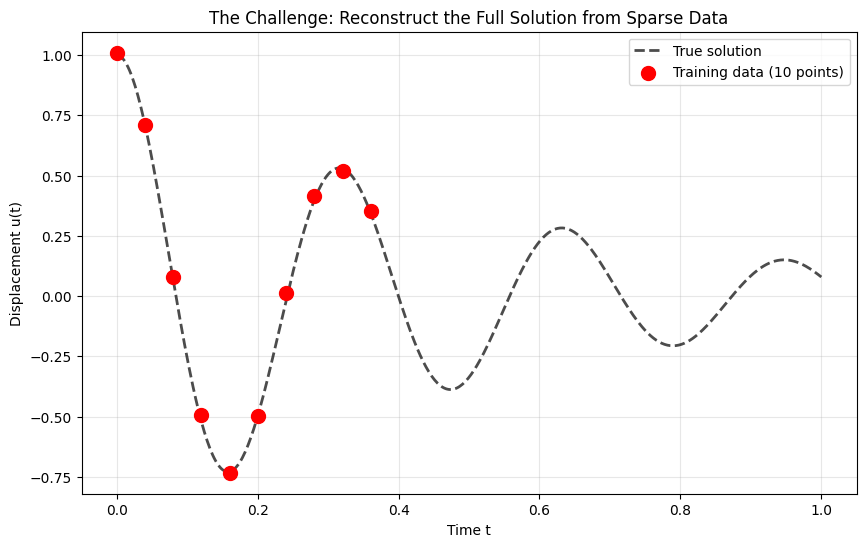

Creating Sparse Training Data

In real applications, we don't have the complete solution. We only have sparse, potentially noisy measurements. Let's simulate this scenario:

CVW material development is supported by NSF OAC awards 1854828, 2321040, 2323116 (UT Austin) and 2005506 (Indiana University)